The Plate above illustrates the main Meissen Trade Marks since 1720

The Story of the origins of the Meissen Crossed Swords Trade Mark

Since around AD 700 China had dominated porcelain making before the discovery of making porcelain at Meissen in 1707. The chemist and and mathetician Einfried Walter Tschirnhaus aided by his protege Johann Freiderich Bottger discovered the formula that would become known as the Arcanum (the secret of making hard paste porcelain in Europe). It would be Bottger who would gain recognition to take away the prize and become known as the inventor of hard paste porcelain only after he made the mistake of convincing Augustus the Strong he could turn clay into gold.

During 1708 after numerous experiments failed that the production to making hard paste porcelain in Europe began in Saxony. By 1710 for security reasons the Albrechtsburg castle in Meissen began the home to making for resale ‘stoneware imitations of Yixing wares popular in China since the Song period of AD 900. It would be a new innovation that Europe had not seen before that hence begun the art of making porcelain, first made in the white and later on around 1720 embellished in the styles of silver and gold vessels so popular in the period.

On the 8th of November 1722 the factory inspector Johann Melchior Steinbruck proposed the use of the electoral swords from the coat of arms of the Electorate of Saxony as a factory mark. Initially the crossed swords mark was used in conjunction with the company’s monogram KPM (not to be confused with the 19th century Berlin KPM) Konigliche Porzellan Manufaktur or KPF ( onigliche Porzellan Fabrik).

The crossed swords mark intended to protect Meissen’s brand had taken twelve years after the factory’s inception in 1710 to become into being. See image of plate above.

Although the trade mark throughout its history has more or less kept its painted form of blue on a white ground(extremely rare examples have been found in purple) with only subtle changes to variation created throughout its history. There are many slight variations of the crossed swords mark as not one mark conforms to a standard length or colour, whether short, long, thick and thin or dark blue, pale blue, etc. The lengths of the handle, hilt and blade of the sword vary. However although there is a standard length the swords should keep to there are often seen subtle variation. The mark doesn’t conform to a standard length or colour, whether short, long, thick and thin or dark blue, pale blue, etc. The lengths of the handle, hilt and blade of the sword vary.Especially on figural wares there can be a difference between the painting of the swords because single figures that make up pairs often became separated. There was no control in the stock room when a customer ordered a pair of figures. The salesman might pick up a pair without checking they are a matched pair. Perfect pairs will have the correct painters no’s on the base whereas matched pairs will have different painters nos. However the major variations of the painting of the crossed swords mark was seen most often in the 18th century when compared to the 19th century.

As an example a pair of figures may have differently painted cross swords marks. The man with one with a long crossed swords mark and the woman with short. Another crossed swords mark could be with the swords painted in dark blue and its pair light blue. See images below for illustrations of variations in painting of crossed swords marks.

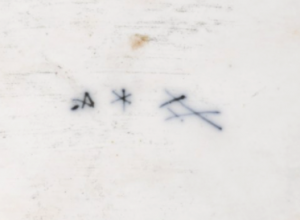

As mentioned above the Cross Swords began its life with the Electorate of Saxony company’s monogram KPM (Konigliche Porzellan Manufaktur or KPF ( Konigliche Porzellan Fabrik).will be found with different variations. This is due to each mark being hand painted.

Also from this early period is pieces that belonged to Augustus the Strong’s personal collection that was housed in the Japanese Palace. Each of his pieces that included both Chinese and Japanese were marked with an inventory no.

For the first forty years from 1722-1763 or thereabouts the crossed swords mark was painted just as how it appears on the porcelain plate pictured above at 15.00 hours.

The blue cross swords would be painted with two long and straight blades, a guard crossing by the hilt(handle). The next main period was called the Kings period and in 1763 the cross swords mark changed and in between the sword handles appears a single dot between each of the hilts.

The Marcolini period (1782-1812) instead of a dot was replaced with a star. But instead of between the handles was painted below from 1774. Seen 20.00 on plate above. The Marcolini mark was replaced in 1815 when the crossed swords mark would stay the same for 109 years till 1924 ready for the Pfeiffer period (1924-34) seen on the plate above 12.00 where a dot sits between the point of the sword blades. Please also see illustrations below that identify with the periods mentioned above. These will include service wares, vases and other objects, figures and groups.

Apart from these three periods there are no distinct differences in the trade mark other than being aware that the crossed swords were painted by hand and not necessarily copied from any official manuscript.

On many of the figural pieces produced by the Kaendler workshop the cross swords mark can be very indistinct due to the limited surface where the cross swords mark could be painted. Particularly during the era of Kaendler the mark would be painted very close to the base but on the back or side; see images and prior to the cross swords mark only the specialist/collector dealer has the education to identify with the unmarked pieces of Bottger porcelain. Bottger porcelain was also used until the early 1730’s and was never marked.

Occasionally some figural pieces made from the 1730’s and well into the 19th century escaped being marked. While during the 19th century between 1825 and 1850 the crossed swords mark can be found so poorly painted that it may not look like a genuine crossed swords and be easily mistaken for one of the many smaller factories . It is much easier to relate to what the cross swords mark looks like when looking at the piece it has been painted on rather than seeing an illustration of the mark.

The following images illustrate both the piece and mark separately.

The Japanese Kakiemon Design plate with a Tiger holds on to an interesting story that can be found by following the link about the first major evidence of Meissen Fraud on a grand scale. The Dutchman’s name is Le Maire who tried to sell off the cheaper Meissen but sell as original Japanese Kakiemon whose value was far higher. The mark is painted over the glaze as opposed to under the base; but for deceitful purposes. Read about the story here.

An early Meissen Teapot bearing K P M. Königliche Porzellanmanufaktur Meissen over a large crossed swords mark. circa 1723-24 This mark only appears on Teapots and Sugar Boxes

Personal Collection of August The Strong

All pieces bearing The Japanese Palace Inventory Marks belong in the personal Collection of Augustus The Strong and are also amongst the earliest marked pieces of Meissen Porcelain.

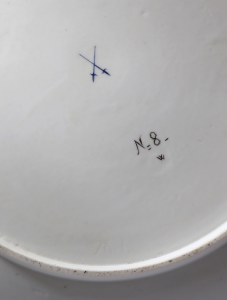

The Large Meissen Saucer Dish 35.8 cm diameter bearing number No 8 circa1729-30 is rather unusual and of a type quite different from other items with inventory nos.

This is because it is also the subject of Meissen Fraud. The Dish was ordered bv the French merchant Rudolf Lemaire who tried to pass off Meissen as the more expensive Japanese Kakiemon. He insisted the crossed swords mark painted in blue enamel was over the glaze as opposed to under(so he could erase the mark).

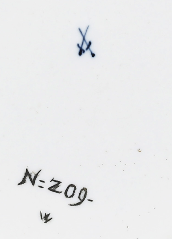

Large Meissen Kakiemon Octagonal Dish 32.4 cm across painted in the Shiba Onto Design. Inventory Mark N=209-W. This means the dish belonged in the personal collection of Augustus the Strong.

The tureen below was the earliest known model; modelled in a style that predates the design that would become traditionally modelled by Kaendler. Circa 1728-1730. However the crossed swords mark is in a rather unusual place. Rather than on the unglazed base or on the decoration to the side, the crossed swords are painted on the centre of bottom of the interior. Tureen in the Chinese Imari PatternDesign.

Meissen Coffee Pot in the Kakiemon style circa 1730.

How the crossed swords mark is painted illustrates the inconsistencies of painting accurately a completely straight sworded mark. That is two lines each as a blade completely straight without any faults such as blobs or dots etc. The fact of the matter this was an impossibility to guarantee a perfectly painted trademark. Its no wonder so many people who see an item whatever it might be, see what appears to be a crossed swords and think MEISSEN made. How wrong could they be because on the crossed swords mark on this coffee pot is a large blob towards the tip of the left blade.

Looking closely at the mark on the Chinoiserie group the crossed swords barely looks like a traditional mark for this period. Yet this is a very good example of how the mark varies. Traditionally the crossed swords should look like the mark on the plate above but it is painted in a very pale blue. It is also possible that the mark has worn down in time given that the base is unglazed. But also the choice of painting next to the hole one wonders why it was painted there as opposed to some other place on the base away from the hole. Perhaps the artist woke up on the wrong side of the bed that day.

Meissen Sadler from the Kandler’s Artisan Series circa 1755 with close-up image of cross swords that hardly looks convincing. It is genuine marks like this that the novice or the new collector/dealer of Meissen can so easily be confused by. Compare to the model of a Coppersmith from the Artisan Series below where the crossed swords mark is almost invisible to the eye appearing more like a blur with a touch of blue than a cross swords.Sa

You can barely see a blue blur that appears under the reflection under the wing immediately above the mark in the 3rd image below.

Photos courtesy of Errol Manners Circa 1750-60

Looking at the figure below this recently came up in a sale at Sotheby’s. The figure had exceptional provenance having been owned by the Mountbatten family.

The description in the catalogue reads; A Meissen porcelain figure of a Dutch farmer’s wife, circa 1752 modelled by J. J. Kaendler, wearing a yellow hat, green jacket and yellow skirt, on a mound base, crossed swords mark in under glaze-blue to rear of base.

While the crossed swords mark can be seen to the rear of the base it is also barely visible. But this is how it is for many figures and groups modelled throughout the early Kaendler period at Meissen between 1735 and 1750.

A pair of Meissen (Marcolini) two-handled oval glass coolers circa 1780-1800 painted with bouquets of flowers 29 cm wide.

Cross swords marks with the star for the Marcolini Period